Image: Suzanne Ouedraogo | Circumcision 2003

The Lost Art

June 26, 2005 Edition 1

Author: Mary Corrigall

Source: The Sunday Independent | South Africa

Web Page: http://www.sundayindependent.co.za/index.php?fSectionId=1088&fArticleId=2598217

What makes an African artefact authentic?

Sacred objects that were once imbued with spiritual and cultural meaning are being mass produced across Africa and sold to tourists.

Stone sculptures, bead necklaces, wooden masks, animals made from wire and beads are being flogged en masse.

Have traditional artworks lost their significance as they gain monetary value? Do tourists still believe that these African knick-knacks are products of cultural expression? What makes an African artefact authentic?

Since the 1880s European colonialists have been fascinated by "primitive" objects produced by traditional African artisans.

This obsessive interest saw explorers, scientists and missionaries importing a wide range of artefacts back to their homelands. These objects were not only offered as proof that a "dark uncivilised world" existed parallel to their own but embodied an alternative belief system.

Most of these artefacts, which were not perceived to conform to western concepts of art, ended up on display in museums of ethnology and anthropology in European centres. Curiosity surrounding these African artefacts would not only kick-start the Modernist movement but came to symbolise a naive and simple way of life that industrialised societies believed they had altogether lost touch with.

Centuries later Africa still draws crowds of curious tourists in search of the stereotypical African experience. Part of this experience also entails tourists taking home their own piece of idealised Africa. African artisans, wishing to profit from tourist preconceptions, are only too happy to comply.

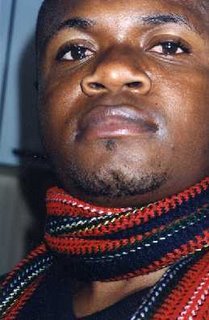

Jozi's Rosebank African Art Market is a popular pit stop for tourists. Lined with stalls selling objects from around Africa, one can pick up a mask from Senegal, a batik printed bolt of cloth from Zimbabwe or an Ndebele necklace.

Joe Flex, from Zimbabwe, has been selling African goods for seven years. His stand is packed with objects to satisfy any taste. Masks from Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone, Mali, Senegal and Congo. He says that he makes two trips a year to West Africa to stock up on goodies.

Flex infers that tourists have become wary about the origins of African objects. They aren't interested in artefacts mass produced in a factory, as that would not conform to their idea that African objects are shaped by primitive and spiritual culture found only in rural destinations.

Flex says that all his products are directly acquired from artisans in rural villages. He is, however, very vague about the makers of his products and how each piece is produced.

According to Flex, most of his clientele ask about the spiritual significance of his wares. Flex can tell a story about every item in his stall. "This is a mask from Ivory Coast," he says pointing to a wooden mask with horns. "It is used during royal ceremonies to pray for rain."

Aside from the masks, Flex sells a wide range of colonial figures.

Flex says that these brightly coloured wooden renderings of Africans in western dress were made in the Ivory Coast during colonisation.

According to Engaging Modernities, compiled by art historians at Wits university, these colonial figures are derived from the Baulé figures from the Ivory Coast, which were designed as a means to engage with spirit lovers in the other world. The emergence of western dress on these figures expressed high status.

Westerners were apparently fascinated by these figures, which were thought to reflect their own image.

As a result the Baulé figures were re-fashioned and carvers expanded their repertoire in the mid-1980s to meet the growing international demand for these wooden figurines.

Flex is a businessman, not an art historian; one would not expect him to know the origin of the objects he sells. However, most of his foreign clients are keen to know the history of an object.

Millicent Sirengo, from Kenya, who also sells at the Rosebank market, says that one can't just make up a meaning about an object to ensure a sale. Some tourists have done a bit of research themselves.

"Customers always ask where an object comes from and what [cultural] meaning it has," says Sirengo wearily.

Most of Sirengo's products hail from Zaire. Sirengo has never been to Zaire. She places her orders for the wooden sculptures over the phone. She asks her suppliers to provide her with details about the products, which she then passes onto her customers.

Although the elongated models of African ladies that she sells are manufactured in Zaire, she gets local Zulu crafters to embellish the figurines with beads. So in essence these objects are not strictly the product of one culture but a synthesis of two different cultures.

Aside from the free-standing sculptures at Sirengo's stall, she sells wooden sculptures of animals and other objects that come framed. The ornate wooden frames that box these wooden sculptures, says Sirengo, make it easier for tourists to display their wooden animals in their homes. This sort of presentation also makes it easier for tourists to perceive the sculptures as artworks.

The goods being sold at Sirengo's stall are not unique; three stalls down, another trader is selling identical artworks.

In a shopping mall, not far from the Rosebank African Art Market, there are a number of curios selling similar goods.

Batanai Artworks is one such shop. However, in this establishment one finds the crafters of the artworks busy at work. Tawanda Marufu, from Zimbabwe, is one of the artists. He says he learnt the craft from his father.

Most of the larger items on sale come with a certificate of authenticity. Marufu says that the certificates were introduced as a way of differentiating their products from the sculptures that are sold at flea markets. The certificate not only authenticates the artworks but it also gives a detailed description about the meaning and origin of the artworks.

Since the introduction of the certificates, Marufu says sales have increased dramatically. Although one can find identical looking sculptures at the market, Marfu says that their products are made from African stone and not soapstone, which makes the artworks more authentic and therefore more valuable. A sculpture that costs around R200 at the market will cost more than R1 000 here.

Marfu says that a lot of the wooden sculptures sold at markets are not made from treated woods; they are merely covered in shoe polish to create a more authentic look.

At Wits university's African art gallery, The Studio, one finds a collection of African artefacts that, based on appearances, do not look too dissimilar to some of the tourist art sold on the side of the road. What makes these artworks collectable, valuable and authentic?

Curator Julia Charlton consults experts to authenticate pieces for the gallery. However, she does suggest that accepted models used to discover authenticity in relation to African art is a contentious issue.

"The kinds of criteria that are usually applied to the concept of authenticity rarely hold up," Charlton says.

"The kinds of things that are usually considered are whether the item was made for use within their own community. But that implies a set of circumstances that are not borne out in the field.

"You may have a ritualist carver whose job it would have been to make ritual objects and he would be known as such, so you would have people coming from far and wide to him to have items commissioned."

Charlton suggests that artworks that are specifically produced for sale to tourists are often deemed inauthentic.

Charlton says that the age of a piece doesn't necessarily guarantee authenticity either; for many of the materials used to make African cultural objects don't stand the test of time, as they were not made to last.

Charlton also proposes that using the age of an artwork as a determining factor to substantiate authenticity presupposes "a static golden past from which there has been a steady slope downhill, which is not real".

Traditional African artworks that have incorporated modern materials or subject matter, Charlton says, shouldn't devalue an artwork either.

The value of an African artwork depends heavily on the buyer. For instance, Charlton says she is interested in acquiring pieces for the gallery that conform to traditional motifs and forms in appearance but have been fashioned out of a modern material like plastic.

Charlton suggests that international art buyers would not consider such an item to be of any value.

Fraud within the African art trade is rife, she says. Charlton says that after a gallery publishes a catalogue of a collection, identical objects copied from the photographs suddenly flood the market.

"Any tourist wants a souvenir, whether it's a postcard or a little something. However, tourists that come to Africa come with a lot of baggage [from the past]."